As the 2014 Indian General Elections draw to a close, now is a good time as ever to apply the marketing lens to the electoral campaigns of the leading political parties and observe their communication strategies.

Indeed, all political parties are forced to think as brand marketers when it comes to running electoral campaigns. They need to identify their constituents and their grievances accurately, target an explicit set of grievances (or the opportunities for value-creation) and provide convincing and persuasive answers to the two fundamental questions of brand positioning: why should their constituents consider them for a vote (as a contender), and why should they actually vote for them.

In elections as complex and long drawn as seen in India, it is near impossible to capture or analyze all communication nuances with their attendant context in a blog post. Our intent therefore is not to provide an exhaustive review; but to pick some standout campaign themes and comment on their effectiveness, with the goal of providing some useful lessons for brand marketers and communications managers. Let us therefore present nine important observations in no particular order.

- Nearly all political parties chose their own positioning with regard to their primary competitors. For principal contenders like BJP and Aam Aadmi Party AAP, this meant choosing a positioning relative to the ruling party – the Indian National Congress (Congress). With the ruling party battling pervasive perceptions of being ineffective, incompetent and corrupt, the opposition parties had a field day choosing and fine-tuning their positioning as completely opposite to Congress’ image.

- All campaigns also play a game of attacking an opposition’s weak points while imitating its strong points. Great political campaigns are invariably built upon high-valued and defensible positioning. Consider how for example Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP’) campaign under Narendra Modi has sought to usurp Aam Aadmi Party (AAP’s) anti-corruption, ‘clean government’ positioning – diminishing AAP’s campaign in return.

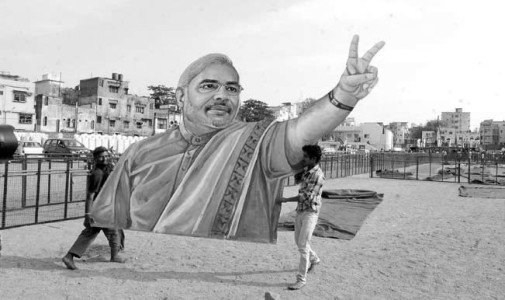

- The BJP ran a focused campaign centered on its Prime Ministerial candidate – Narendra Modi. This choice was largely dictated by two reasons: a highly-lucrative positioning opportunity (anti-corruption, effective and competent governance) as mentioned in the bullet above, and the fact that Narendra Modi, as Gujarat Chief Minister, had ran a campaign with the exact positioning for many years, albeit for entirely different reasons. For BJP, it was a rare opportunity to take the valuable anti-corruption plank. Further, it simply had to take Modi’s existing and successful, but localized campaign and amplify it at the national level. Marketers with a large global portfolio of brands would find this stratagem extremely familiar.

- However, in choosing Modi as the face of its campaign, BJP ran a heavy risk of alienating a substantial section of Muslims and liberals. This was because of negative perceptual residues of Modi as a ‘communal’ administrator who allegedly oversaw the 2002 riots in Gujarat, where over 1,000 people were killed. Applying segmentation principles skillfully, the BJP appeared to have taken a bet that the size of the segments who would value Modi’s positioning as head of a efficient and competent government who is also anti-corruption is significantly bigger than the segments that Modi would alienate. In other words, BJP has deliberately focused on certain segments while ignoring others – the defining hallmark of a great marketing strategy.

- The Congress’ campaign ran in stark contrast to BJP’s razor sharp segmenting, targeting and positioning. Their positioning itself is built on two different planks: the first as relative to BJP (consider the message ‘Kattar soch nahi, yuva josh’) and highlighting its focus on inclusive growth (‘Har haath Shakti, har haath tarakki’).

- The campaign messages of the BJP and the Congress also readily reveal the voter segments they are reaching out to. The BJP’s campaign messages appear to be designed for India’s middle and upper classes – estimated to cross 250 million in number by the next year – with the promise of economic growth and jobs and the core theme of competent and effective governance. The Congress campaign with its ‘…Har Haath Tarakki’ message and imagery appears to be targeted at rural and low-income constituents – much larger in numbers compared to the middle and upper class constituents. Purely in terms of the size of segments targeted, the Congress has a decisively upper hand.

- The above also partly explains why BJP’s print and TV media spends have dwarfed those of the Congress – for the Congress seems to have relied more on doles and payouts (channel management and BTL in marketing terms), as compared to an ATL ad blitz, to win its targeted rural or low-income constituents. This is a well-thought out strategic move.

- Unfortunately, the above also means that whatever media spends the Congress has incurred to reach or influence the middle and upper classes have been let down by their poor positioning. In other words, the Congress has not been able to articulate a strong enough value-proposition to the middle and upper-classes, a fact betrayed by its creative strategy (consider the message: ‘Kattar soch nahi, Yuva Josh’). One big reason why this positioning falls flat is that the audience simply refuses to identify with the ‘weak points’ of BJP as highlighted by Congress (‘Kattar soch’), or even with the differentiation that the party offers (‘Yuva josh’). Indeed, many of the messages deployed by the Congress appear to run counter to prevailing popular beliefs and opinions.

- The Aam Aadmi Party burst upon the political horizon with a truly disruptive positioning hinged on a single attribute – anti-corruption. It’s greatest success was in introducing a completely new dimension in electoral rivalry – for all incumbent parties battled perceptions of corruption in varying degrees. Later, AAP sought to widen its positioning by taking the anti-entitlement plank. However, it also learnt the hard way the potential pitfalls of using a sharp positioning, as opinion polls clearly suggest that the segment that values this positioning is significantly overshadowed by the segment that values BJP’s positioning of Narendra Modi that combines anti-corruption messaging with competence and effective governance. AAP could have been a much strong contender if only it could imitate and neutralize BJP’s ‘competent, effective governance’ plank. This is why AAP’s self-dissolution of its state government in Delhi earlier this year will count as a strategic blunder.

Finally, it is perceptive to see the genesis of the current BJP campaign over how the public mood had polarised over the last few years. There had been a steadily growing clamour for a competent, incorruptible, even ruthless political leader who can run a streamlined administration. In the early years, a stream of China-India comparison stories, Op-Eds and even books fueled this clamour. Steadily, this clamor grew and took form across the Indian social landscape, from the boardrooms of India’s largest companies to the drawing rooms of a growing middle-class.

The greatest success of the BJP in 2014 has been to pin this clamor down to its precise specifics and craft a product that scores very high on those very specifics – in the form of its PM candidate. In other words, the people wanted a specific style of leadership, and only BJP delivered it (the AAP made a good start but couldn’t sustain it). This, dear reader, is a critical marketing takeaway from the 2014 Indian Elections.

(Photo credit: India.com)